Wild Boys of the Road stands out as a quintessential pre-Code film—unflinching in its depiction of poverty, juvenile delinquency, and the failure of societal institutions during the Great Depression. Released in 1933, just before the enforcement of the Hays Code would begin censoring morally controversial material, the film explores themes that would soon be deemed too provocative for mainstream Hollywood. It portrays teenagers hopping freight trains, stealing food, living in squalid hobo jungles, and clashing with brutal railroad police—all stark reflections of the economic desperation that defined the era. Rather than sanitizing its subject—well, at least until the very, very end—the film exposes the conditions that drove young people to the margins of society, often resorting to petty crime as a means of survival, highlighting how American institutions repeatedly failed the nation’s most vulnerable citizens.

During the Great Depression, an estimated 250,000 young people became hobos, traveling across America in search of work and a better life. Driven by economic hardship and family instability, many fled homes fractured by unemployment and hopelessness. These young drifters set out in search of opportunity but more often encountered only further hardship. Their plight was emblematic of a broader domestic crisis, as families across the country buckled under the weight of mass unemployment and economic collapse.

Warner Brothers set out to dramatize the story of these lost children. Wild Boys of the Road vividly captures the widespread poverty and despair of the era through a child's eyes. It follows two teenagers, Tommy and Eddie, who choose to leave home in order to ease the financial burden on their struggling families.

Eddie, played by Frankie Darro, begins as a carefree teen devoted to his friends, his jalopy, and his family. He’s living his 1930s version of the American Dream. For Eddie, the Depression feels like something happening to other people. He starts the film enjoying a comfortable and secure home life.

In contrast, his best friend Tommy (Edwin Phillips) begins the story already overwhelmed by the toll that inconsistent work and financial strain have taken on his widowed mother. He feels like nothing more than a burden to her.

Eddie’s world is upended when his father loses his job, forcing the family to adjust to a new and frightening reality. In an effort to help, Eddie sells his beloved car to support his family. But feeling it’s not enough, he and Tommy decide to leave home, hoping to ease the financial burden on their households and find work on the road. Along their journey, they join a group of homeless young vagabonds crisscrossing the country in search of safety, stability, and a square meal. These half-starved, grimy teenagers navigate life in isolation—hopping overcrowded freight trains, evading violent railway police, and surviving in improvised shantytowns.

They soon befriend Sally, played by Dorothy Coonan (Director William Wellman’s wife and a former Busby Berkeley chorus dancer), a resourceful girl who, seeing herself as one more mouth to feed, has left her family of nine in Seattle and is trying to reach her aunt in Chicago. Sally wisely has disguised herself as a boy, knowing instinctively the dangers associated with traveling openly as a female.

Naïve and optimistic, the boys expect adventure; instead, they are quickly overwhelmed by the harshness of life on the rails. Between 1929 and 1939, thousands of young "children of the road" died in accidents, fell victim to crime, or succumbed to disease and malnutrition. Railroad police, known as "bulls," were infamous for their cruelty, often beating or killing trespassers. Hobo jungles, plagued by violence and sickness, offered little refuge.

As one real-life hobo, Robert Lloyd, recalled:

"I saw more than one hobo just give up and drop from a train to his death when the train was moving fast. And I saw the time when it was hard not to follow their example, for hunger will cause a man to do things he would never think of with a full belly. But pride, or maybe the lack of guts to do so, kept me from it."

Sally and fellow female hobo Lola (Ann Hovey) add another layer of pre-Code realism to the film. As girls on the road, they face heightened risks of sexual violence and exploitation—a danger the film acknowledges with restraint but unmistakable urgency. Like Sally, many young women during the Depression disguised themselves as boys for protection; others were forced into degrading choices simply to survive. These frank depictions of vulnerability and abuse would be softened—or erased entirely—in films made under the Hays Code.

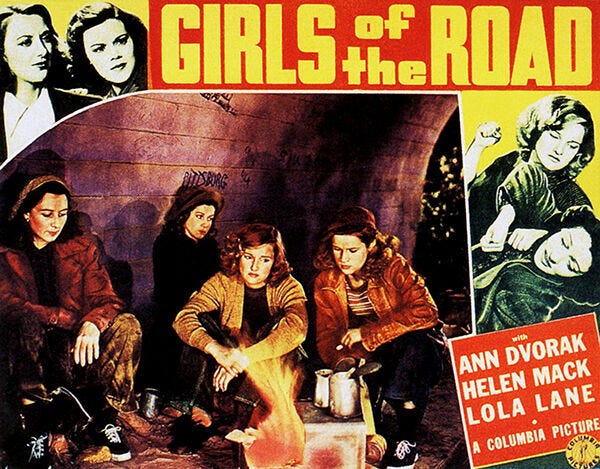

For example, Columbia’s Girls of the Road (1940), starring Ann Dvorak, Helen Mack, and Lola Lane, presents a similar premise but with a far more sanitized tone. That film follows a group of young women riding the rails in search of stability, work, and even love. The gritty realism seen in Warner Brothers’ 1933 output is replaced with a more palatable—and at times romanticized—depiction of poverty and camaraderie. Where Wild Boys of the Road ends with Eddie delivering a searing indictment of adult society in a courtroom, Girls of the Road frames its characters’ struggles as the result of poor personal choices, rather than broader societal or systemic failure.

This contrast underscores what makes Wild Boys of the Road so remarkable: it shows how economic desperation can unravel stable social structures, then turns a calculating eye on the way society treats those it has abandoned. Eddie and Tommy are ordinary middle-class kids—until they're not. In the 1930s, being middle-class typically meant having a modest home, one working parent, and a sense of financial security. But that stability was precarious. As jobs vanished and wages were repeatedly slashed, families who once lived comfortably found themselves unable to afford even the basics—forcing some young people to take extreme, and at times misguided, measures in an effort to help their loved ones survive.

Eddie and Tommy begin their journey with optimism. They believe they'll find work and make a difference. But instead, they encounter a world defined by crime, exploitation, and institutional neglect. Over time, their youthful hope is eroded, replaced by mistrust and disillusionment. Director William Wellman originally envisioned a grim ending, with the kids sent to jail or reform school—a conclusion truer to the era’s realities. But studio head Jack Warner insisted on a more hopeful resolution, and he prevailed. So instead of punishment, the film closes with the idealistic and false promise of redemption and family reunion.

Yet despite its upbeat conclusion, Wild Boys of the Road remains one of the era's most searing depictions of youth shaped by crisis. It honors the resilience, camaraderie, and hard-won wisdom of a generation that came of age on the rails, offering a poignant lens into how the Great Depression fractured the very foundation of family, community, and trust.

and finally. . .

Cinema Cities and the Screen Spectator is a one woman show written, produced, edited, researched, designed all by me, Sydney. If you’re loving this content please consider supporting Cinema Cities and The Screen Spectator by becoming a paid member of this substack (you get cool extra stuff) or clicking here and joining my Patreon⭐️ (same cool extra stuff as the paid substack)

You can find a list of essential Cinema Cities books and movies here: Cinema Cities Favorites

Email: CinemaCities1978@gmail.com

Warner Brothers at that time had the reputation as the studio that seemed most connected with the urban proletariat; even its animated characters displayed urban confidence. This film falls into their pre-occupation with ordinary people in harsh circumstances, depicted in a more adult manner in "I Am A Fugitive From A Chain Gang".

It's a far cry from what it has now become.

I was fascinated by Wild Boys of the Road, for the reasons you wrote. Yes, movies dramatize, but you learn a lot about history by what they thought was relevant to their audiences. So yeah, sexual assault of young women was taken as a given, a shocking thought to anyone who wishes to turn the clock back to a “gentler” time.