The Movies that Made Me #1 - From This Day Forward (1946)

To celebrate my birthday (July 1), I'll be spending the next two months revisiting some of my favorite under-the-radar films—movies that have lived rent-free in my head and heart for three decades.

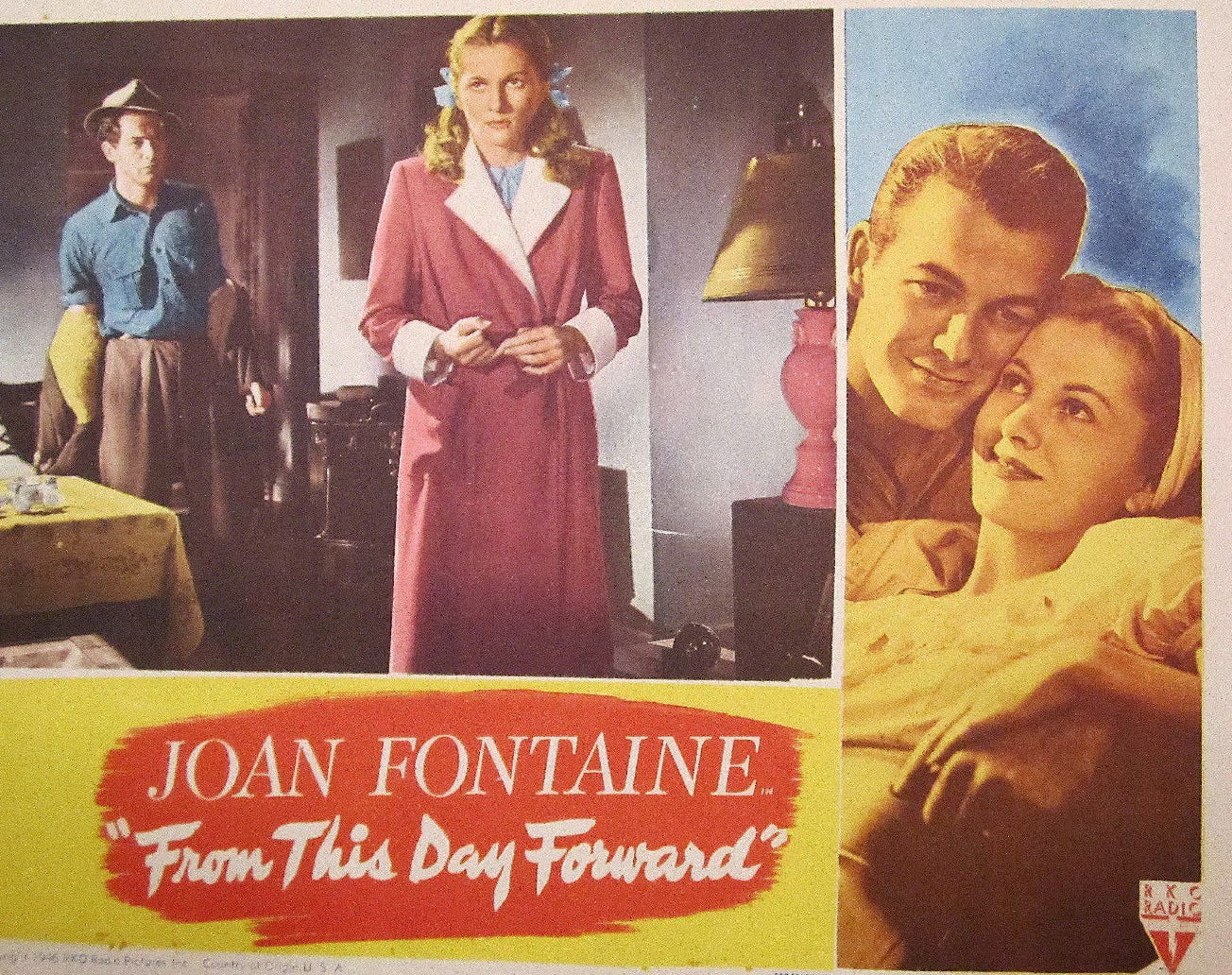

From This Day Forward (1946), based on the 1936 novel All Brides are Beautiful by Thomas Bell, directed by John Berry and starring Joan Fontaine and Mark Stevens, is a quiet yet emotionally resonant entry in the cycle of postwar Hollywood dramas that sought to grapple with the new American reality. Released by RKO during a period of deep social and economic transition, the film belongs to a wave of so-called “message movies”—Hollywood’s socially conscious dramas of the mid-to-late 1940s that confronted the struggles of ordinary people with moral seriousness and stylistic restraint (examples include Pinky, Crossfire, The Snake Pit). While many such films focused narrowly on the immediate aftermath of World War II, From This Day Forward broadens the lens. It tells a story not just of postwar uncertainty, but of endurance across eras—tracing the hardships of a working-class couple from the waning years of the Great Depression through the uneasy return to civilian life after the war.

At the center of the film are Bill and Susan Cummings (Mark Stevens and Joan Fontaine), a young couple whose love story unfolds not in sweeping romantic arcs, but in a series of modest, deeply human moments. When the film begins, Bill has just come home from military service, eager to work, build a life, and find some version of the American Dream. But jobs are scarce, housing is expensive, and the world he left behind has changed in subtle but disorienting ways.

Like many returning veterans, Bill turns to government programs such as the U.S. Employment Bureau, created to help soldiers reintegrate into the workforce. Yet the film captures the gap between good intentions and lived reality. The employment office scenes crackle with frustration—men crowding into overheated rooms, repeating their qualifications, being told to “fill out these forms, soldier.” Many of them, like Bill, were trained for frontline tasks and now find their prewar jobs filled by others. Their patience is thin, their hope threadbare. In one particularly affecting moment, the crowded room of loud, annoyed, and exhausted men suddenly falls silent as a thunderstorm kicks up outside. The boom of thunder and flash of lightning brings a wave of unspoken memory; it's made clear, without exposition, that every man in that room has just been pulled back to the battlefield in his mind. It’s a haunting reminder of how close the war still lingers, not just in the body, but in the nervous system.

Through a series of flashbacks, we come to understand the emotional weight of Bill’s struggle—not only as a veteran, but as a man who has already spent years fighting for basic dignity during the Depression. The film offers a rare continuity: the economic hardship of the 1930s bleeds into the social and emotional uncertainties of the late 1940s, creating a portrait of working-class life that is unusually grounded for the studio era.

The film’s emotional core is Bill and Susan’s relationship—quiet, resilient, and deeply rooted in the rhythms of everyday life. He’s a precision machinist; she works in a modest bookshop. He’s gentle brawn; she’s practical intelligence. Their romance is not grand or ostentatious, but deeply felt and believable. They walk across the High Bridge hand in hand, attend dances at the local political hall, navigate small disagreements with stubborn forgiveness, and spend their evenings at the movies or visiting with family. Their love isn’t built on sweeping gestures—it’s built on showing up, on knowing glances, and on a shared understanding of life’s limits and quiet joys. In the hands of director John Berry, their ordinary life becomes something beautiful. The simplicity of their love makes it feel more profound; it becomes the emotional anchor around which wider history unfolds.

This emotional center finds its most poetic expression during a dance held at a modest union hall. It’s not a grand or symbolic moment—it’s a neighborhood gathering, full of working families and familiar faces—but it becomes one of the film’s most memorable scenes. A singer takes the stage ( an uncredited Doreen Dryden) and performs the film’s title song, “From This Day Forward,”written by Leigh Harline and Mort Greene. The song doesn’t just underscore the scene—it becomes a lyrical expression of Bill and Susan’s devotion, a musical mirror of the life they’re trying to build.

From this day forward, I promise you with all my heart

That we shall never be apart, from this day on

From this day forward, I'm yours to call your very own

I live my life for you alone, from this day on

On and on, I'll welcome each new tomorrow

Knowing that our tomorrow is here

On and on, and even beyond forever

Heaven is mine whenever you're near

From this day forward, I give you me with all my love

From this day forward, from this day on

It’s a love song without irony—plainspoken, heartfelt, and completely in tune with the emotional texture of the film. As the lyrics float over the crowd, there’s a quiet sense that every note belongs to Bill and Susan. Their story, like the song, is about choosing one another again and again—not in fantasy, but in the small moments that define a life. The scene feels almost sacred in its simplicity. And in John Berry’s hands, that simplicity becomes something luminous. This is a deeply romantic film precisely because it never tries to sell a fantasy—only something true.

Keep reading with a 7-day free trial

Subscribe to The Screen Spectator to keep reading this post and get 7 days of free access to the full post archives.