The Things We Lost in the Fire

On the early morning of July 9, 1937 the 300 block of Main Street in Little Ferry, New Jersey, was quiet. Although it was a residential neighborhood, the five houses on that square block surrounded a squat, red-bricked commercial building measuring three hundred by one hundred feet.

Owned by Deluxe Laboratories and rented by 20th Century Fox, the building stored forty thousand reels of film prints and negatives, all on nitrate film stock belonging to both Fox and Educational Pictures

Inside the building, there were 48 individual vault rooms, each secured by a steel door and separated by 8-inch brick interior walls, and twelve-inch-thick outer walls. The roof was made of reinforced concrete. Although certified as fireproof, the vault did not have automatic sprinklers or a ventilation system.

The steel doors, reinforced roof, and thick walls were not excessive precautions. The storage of nitrate film required extreme care. In use until 1952, nitrate film stock was the industry standard. Its cellulose base and the silver in its photographic emulsion produced crisp, pristine images with deep blacks, bright whites, and a silvery sheen in its grays. Nitrate film offered rich tonal detail and sharp contrast for black-and-white motion pictures, as well as dazzling, deeply saturated color when used with Technicolor or other color film processing technologies.

Images projected on nitrate film were said to leap off the screen with a three-dimensional quality. However, for all the beauty nitrate film offered, it had a dark and dangerous downside: it was highly combustible.

Composed of cellulose nitrate, over time, which can begin within ten years (the films in the Fox vault ranged from five to twenty-three years old), the film undergoes a slow and self-sustaining chemical decomposition. As the film ages, it releases nitric acid vapors that can react with the cellulose nitrate itself, breaking down the film into more unstable compounds.

This decomposition generates heat, and if this heat is not dissipated or if the film is stored in conditions where it cannot safely release heat, it can reach a point where the film ignites spontaneously. Once ignited, nitrate burns hotter than gasoline and emits toxic fumes. A nitrate fire cannot be immediately extinguished because the combustion process generates its own oxygen, enabling it to continue burning even underwater.

July 1937 was scorching hot. For weeks, the Mid-Atlantic and East Coast endured a heat wave, with daily high temperatures hovering around ninety degrees with little relief. Inside the Fox vault, forty thousand reels of film sat cooking. At 2 a.m. on July 9, 1937, a combination of gases produced by decaying film, the relentless high temperatures, and inadequate ventilation led to the spontaneous combustion of the film stored at 365 Main Street.

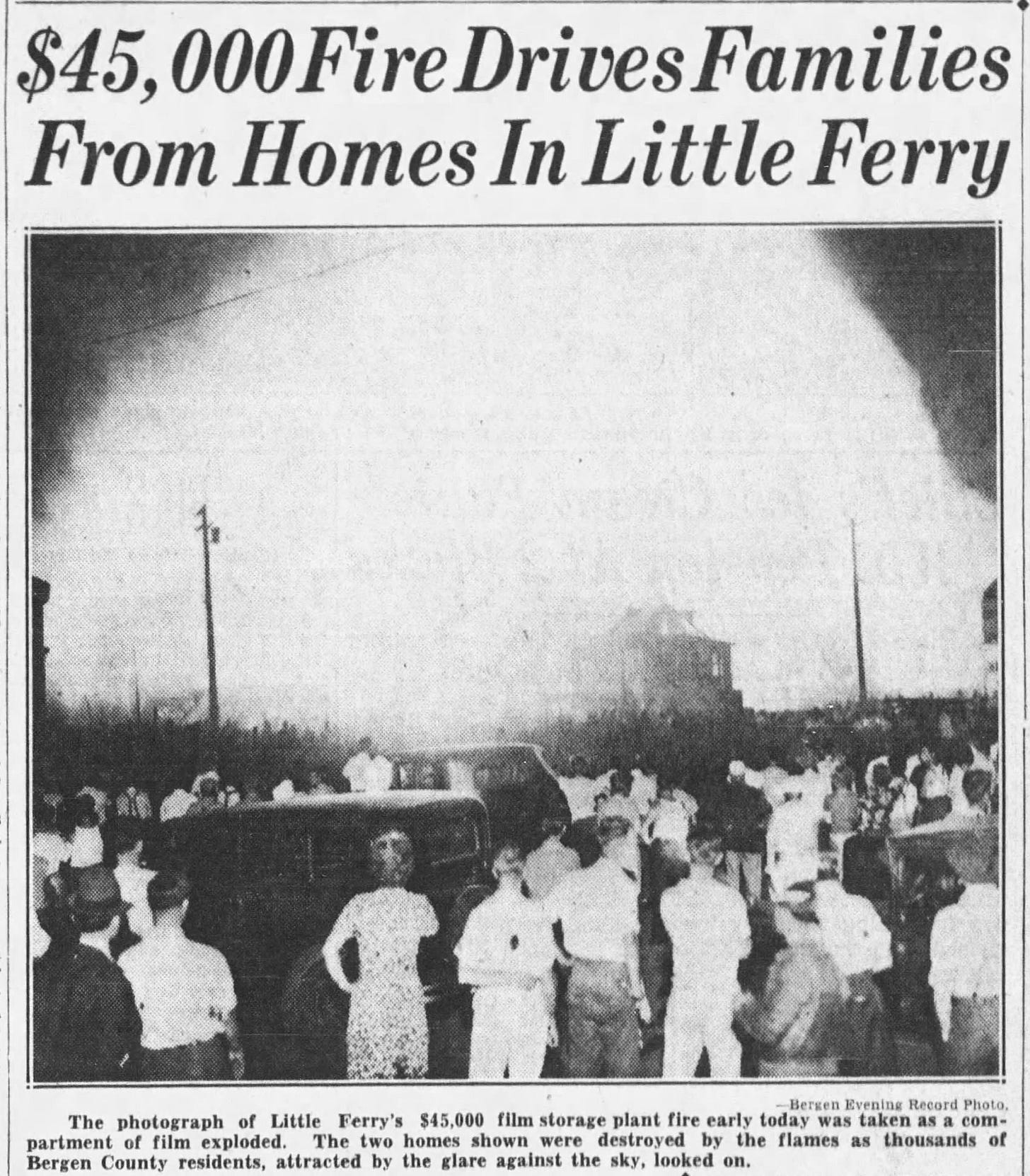

As the vaults burned and the nitrate film ignited, explosive flames shot out 100 feet from the building through its windows and roof. A series of blasts blew out windows in the surrounding homes. The residents living next to the vault, awakened by the heat and noise, ran for their lives.

One witness said the fire, "looked like a blowtorch shooting into the air."

Film of the fire burning in Little Ferry New Jersey

The vault's caretaker, Louis Bossano, who lived closest to the building, managed to escape with his wife and children. Mrs. Anna Greeves, fleeing her burning home with her three children, dropped her daughter Patricia as they ran to safety across the street. Anna, along with her two sons, John (12) and Charles (13), received first-degree burns when a sheet of flame burst from the burning building.

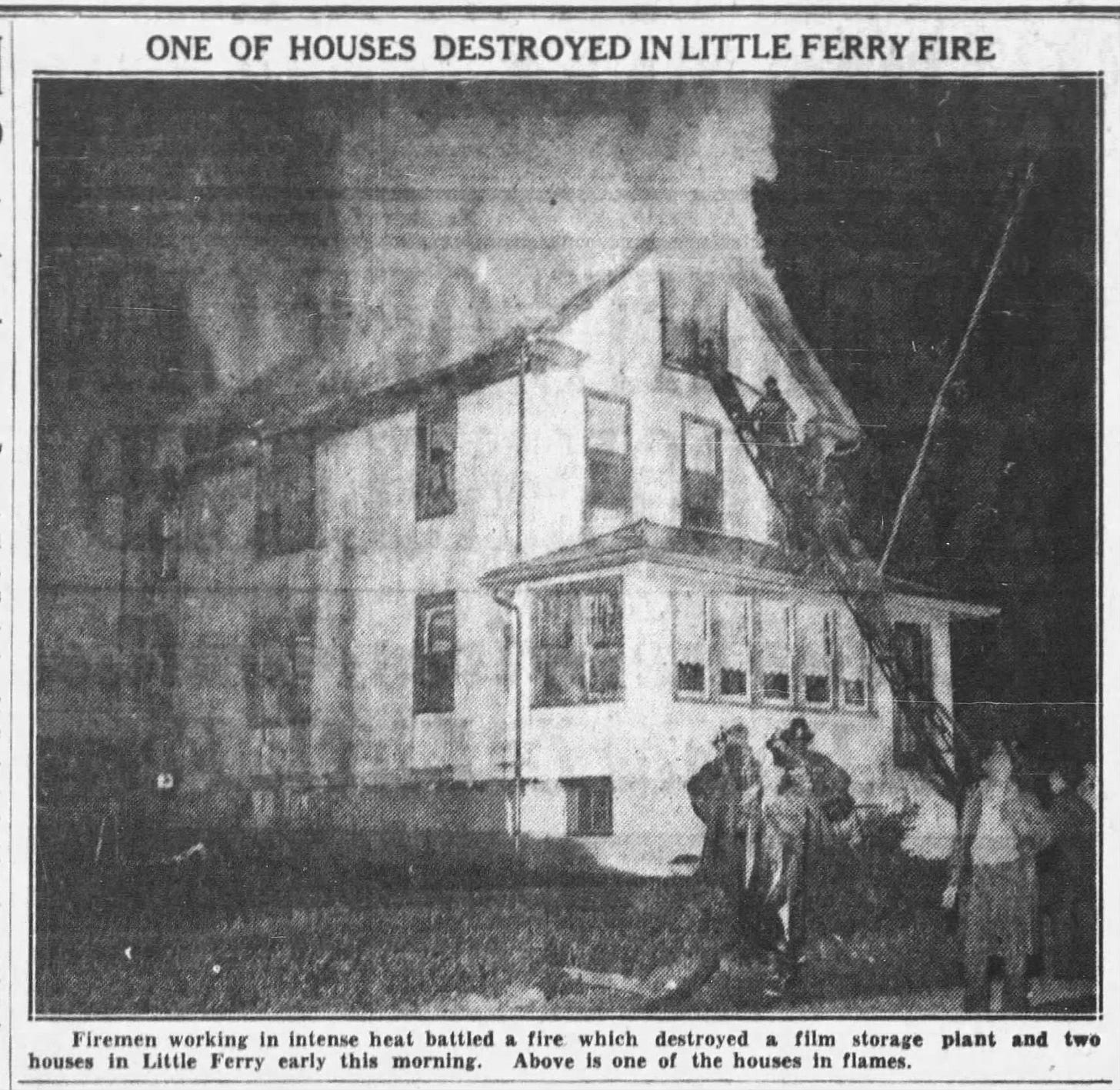

The first firefighters arrived on the scene within twenty minutes, but they were confronted with such intense heat that they could not get close enough to use their hoses. Buildings as far as 1000 feet away caught fire, and the flames burned so brightly that they were visible several towns over. Neighboring fire departments from Hawthorne and Ridgefield Park rushed to the scene in Little Ferry to help battle the blaze. As a crowd of thousands gathered to watch the conflagration, flying pieces of flaming debris rained down on them and nearby residences.

Firefighters from five separate districts worked until 8 a.m. to extinguish the fire. The blaze destroyed the vault and all of its contents. The Bossano's home was reduced to ashes, along with a two-family flat on the corner. Two cars, a pigeon shed, and several garages were also destroyed. The Greeves' home was saved, as was the home of their neighbors, Mr. and Mrs. Roberts, whose house was scorched, with every window either cracked or blown out.

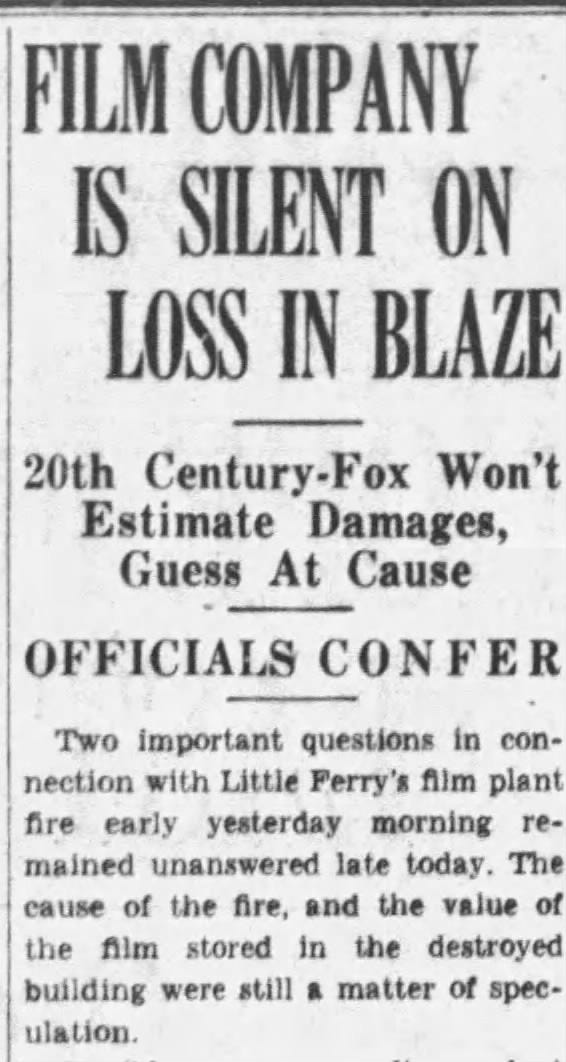

In the following days, Fox's initial response to the fire was surprisingly blasé. They said the vault contained nothing but old film, and the studio estimated their loss at $15,000, the value of the silver that could have been extracted from the film had it not been destroyed. The total estimate for all lost and damaged property was estimated to be between $200,000 and $500,000.

But as early as July 10, the day after the fire, reports began to surface that many of the lost films were the only copies in existence. Fox representatives denied that the vault held the sole copies of the films stored inside and told the press that the films lost in the fire were limited to those released in the past three years. In reality, the vault at Little Ferry contained the camera negatives and the fine-grain masters of seventy-five percent of Fox films made before 1932.

Ideally, for safe and secure preservation, a fine grain master—which is a high-quality duplicate made from the original negative, and used to limit the number of copies made from the original negative and to produce release prints, thus preserving the original negative for archival purposes—would be stored in a location separate from the camera negative, ensuring that there were at least two high-quality sources to strike new release copies of a film. The choice to store the negatives and the masters in the same vault resulted in the destruction of all existing copies of hundreds of Fox films.

An immediate result of the fire was the instantaneous obliteration of the work and legacy of many silent film Fox stars and directors. Complete or nearly complete filmographies of stars like Theda Bara, the original Vamp, were lost. Theda Bara, one of the silent screen's biggest sensations and a pop culture phenomenon, made a total of forty films, and today, only two survive in their complete form. Her lost films include extravagant adaptations of 'Camille,' 'Romeo and Juliet,' 'Salome,' and 'Cleopatra' (only one minute of this film still in existence).

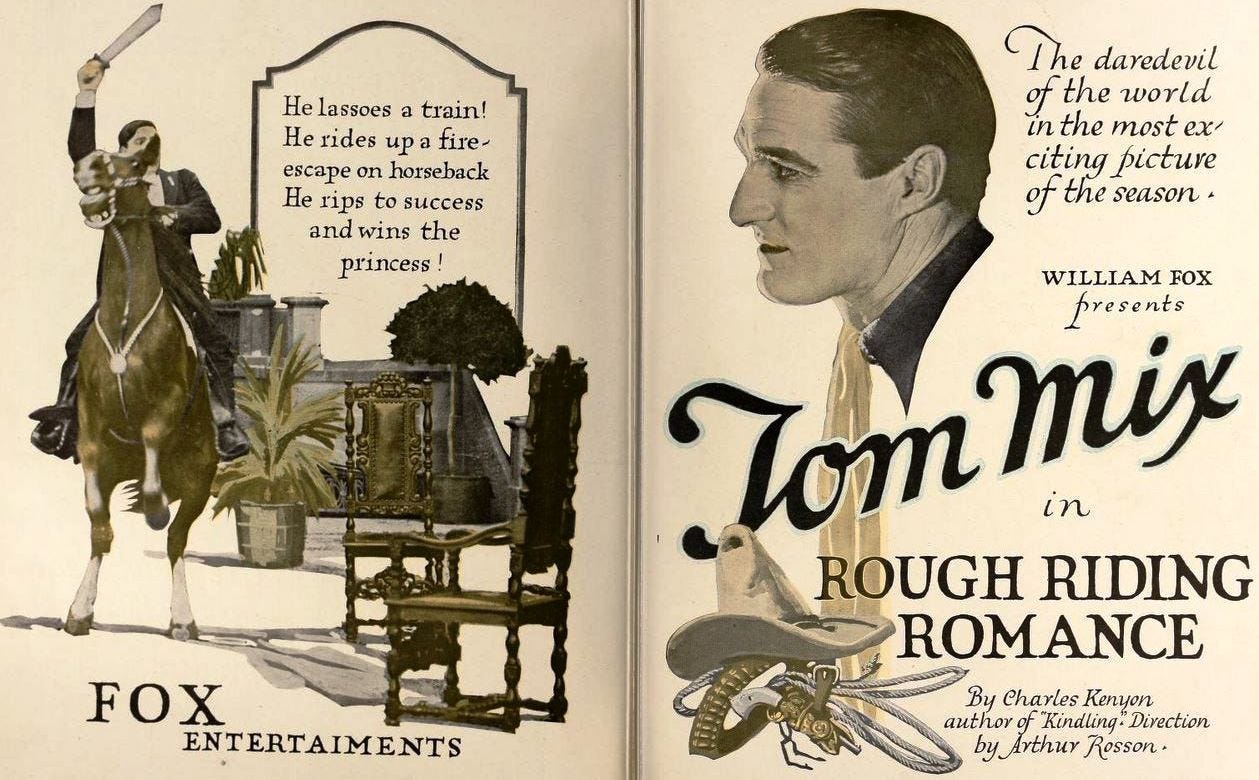

Western star Tom Mix, known to his fans as the King of the Cowboys, made over 200 films during his career, 85 of those at FOX, and only twelve of his FOX westerns survive.

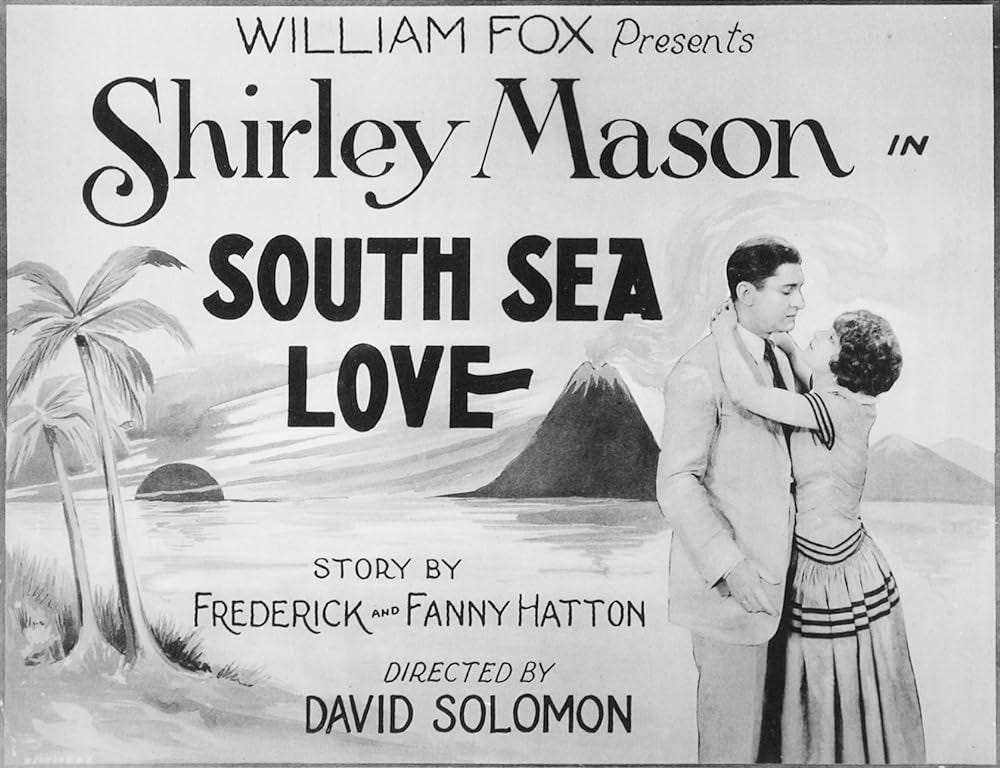

Tom Mix fared better than Shirley Mason; all sixteen films she made for FOX were lost.

Valeska Suratt's entire body of film work was destroyed, leaving her without any screen legacy.

Top box office Fox child stars and sisters Katherine and Jane Lee, known as the baby Bernhardts, both appeared in several of Theda Bara's lost films as well as their own. They made thirty-three films and short subjects between 1914 and 1919, and all of their feature films were destroyed in the Little Ferry fire.

Actress June Caprice, one of the studio’s most bankable stars of the late teens, made all but six of her twenty films at Fox, and every single one of her Fox films was lost. Only four of her films made for other companies survive today.

Her husband director Harry Millarde's entire body of work is gone except for one film, "Over the Hill to the Poor House" (1920). The only copy known to exist is in a film archive in France.

The Fox fire was not the first film vault fire, and it was not the last. In fact, in 1914, two major fires destroyed the film libraries of major corporations. The Lubin Manufacturing Company's vault in Philadelphia exploded on June 13, followed on December 9 by a fire that destroyed Thomas Edison's laboratory complex in West Orange, New Jersey.

In a way, these fires were catastrophic manifestations of a much larger problem. The individuals in charge of these film libraries saw no real value in them. They were aware that the film degraded, knew it was highly flammable, and they had no interest in covering the cost of building adequate facilities to keep their old motion pictures safe. To studio executives, these were forgotten movies that no one wanted to see, and there was no profit in saving them, only expense.

Some studios did not need accidental fire to dispose of their older films. They were thrown out, mined for their silver content, or intentionally burned to make space in storage facilities and office buildings. There is a long-standing rumor that Harry Cohn of Columbia Pictures threw out the studio's silent films because the fire insurance premiums were scheduled to increase. Sam Goldwyn's wife, Frances Howard, discarded Goldwyn's entire silent library except for one film, "The Winning of Barbara Worth" (1926), which co-starred Gary Cooper, so she believed it had some value.

Over the years, the flames, neglect, indifference, and short-term thinking combined to all but erase the legacy of silent films from popular American cultural history. Once the last generation that regularly saw these films in theaters passed away, their place in the public consciousness essentially vanished.

Although the industry switched from nitrate to cellulose acetate film, or safety film, in the 1950s, preservation efforts were slow, and vault fires continued to ravage film archives and storage facilities.

Today, only 14 percent of American silent feature films (1,575 out of 10,919 titles) survive in their original, complete 35mm copies. Another 11 percent (1,174) also exist in complete form, but in less-than-ideal editions, such as foreign-release versions or small-gauge formats like 16mm.

Silent films were a crucial part of early 20th-century culture and entertainment. Their loss means that a substantial part of our cultural heritage has disappeared. These films reflected the social, political, and artistic trends of their time, providing insights into the era's values and norms. The loss of these films also hinders the study of film history and limits our ability to fully appreciate the artistic and technical achievements of that era.

Fox vault fire was one of the worst in terms of cultural and historical loss and resulted in one death. Twelve-year-old Jon Greeves later died from the injuries he sustained that night. After the flames were extinguished, and the area was declared safe, the seven families who lived on the 300 block of Main Street returned to rebuild.

Today, the site of the Fox vault is occupied by two raised ranch-style houses.

Further Reading:

Vamp: The Rise and Fall of Theda Bara by Eve Golden

Silent Movies: The Birth of Film and the Triumph of Movie Culture by Peter Kobel

Silent Stars by Jeanine Basinger

Film Losses Due to Vault Fires:

(data compiled from contributors to TCM message boards )

1914 - Lubin Fire (Philadelphia):

Destroyed Oliver Hardy's film debut.

Lost footage of McKinley's ambulance leaving the Expo after he was shot.

Hobart Bosworth's version of The Sea Wolf also lost.

1914 - Los Angeles:

The lab shared by Keystone and Ince Films had a fire, resulting in destroyed films.

1915 - Edison's Vault:

There may have been a fire affecting Edison's vault.

1924 - Universal (East Coast) Vault Fire:

Negatives to Universal films from 1913-1924 were destroyed.

1933 - Warner Bros/First National Vault Fire:

Most of the 1928-1930 Vitaphone talkies were lost.

1937 - 20th Century-Fox (NJ):

Negatives for most, if not all, pre-1935 Fox films were destroyed.

Films lost included Cleopatra starring Theda Bara and Way Down East, as well as works by William Farnum, Harry Carey, and Tom Mix.

Also, companies like Educational Pictures and World-Wide, which Fox sub-distributed for, suffered losses.

1940s - Museum of Modern Art (Multiple Fires):

Four major vault fires, one of which wiped out 2/3rds of the collection.

Included losses like Hans Richter's hand-painted color animation Rhythmus 25.

1943 - Harold Lloyd's Personal Vault:

Losses included the Lonesome Luke series and the original camera negative of Safety Last!

c. 1950s - RKO Vault Fire:

Resulted in the loss of Citizen Kane and other RKO titles, including Case of the Sgt. Grischa, Freckles, Laddie, Leathernecking, The Monkey's Paw, West of the Pecos, White Shoulders, Hit the Deck (only the soundtrack survives), and Runaround.

1959 - Cinémathèque Française Vault Fire:

Destroyed films, including Von Stroheim's The Honeymoon.

1961 - 20th Century Fox's New Jersey Vault Fire:

Lost most of Theda Bara's work.

1965 - MGM Vault Explosion and Fire:

Destroyed the entire contents, including films like A Blind Bargain, The Divine Woman, and London After Midnight.

1967 - National Film Board of Canada Vault Fire

1993 - Henderson Film Lab Fire (London):

Destroyed the original negatives of Satyajit Ray's Apu Trilogy and Ealing Studios Comedies.

Non-Fire Destruction:

1948 - Universal Silent Library Purge:

Universal decided to discard its silent film library, destroying films, screen tests, and trailers to recover their silver content.

Decomposition:

Many films have been lost to natural decomposition.

Survival Rates:

Paramount produced around 1200 silents, but only about 250 survived by the late 1960s.

Fox produced about 1200 silents, and only about 120 are believed to still survive.

Warner Brothers' silent library also suffered significant losses.

MGM silents from 1924-1929 seem to have the best survival rate.

Less than 20 of the 1917-1922 Goldwyn silents are believed to have survived.

Upcoming October Blu-Ray/DVD Releases

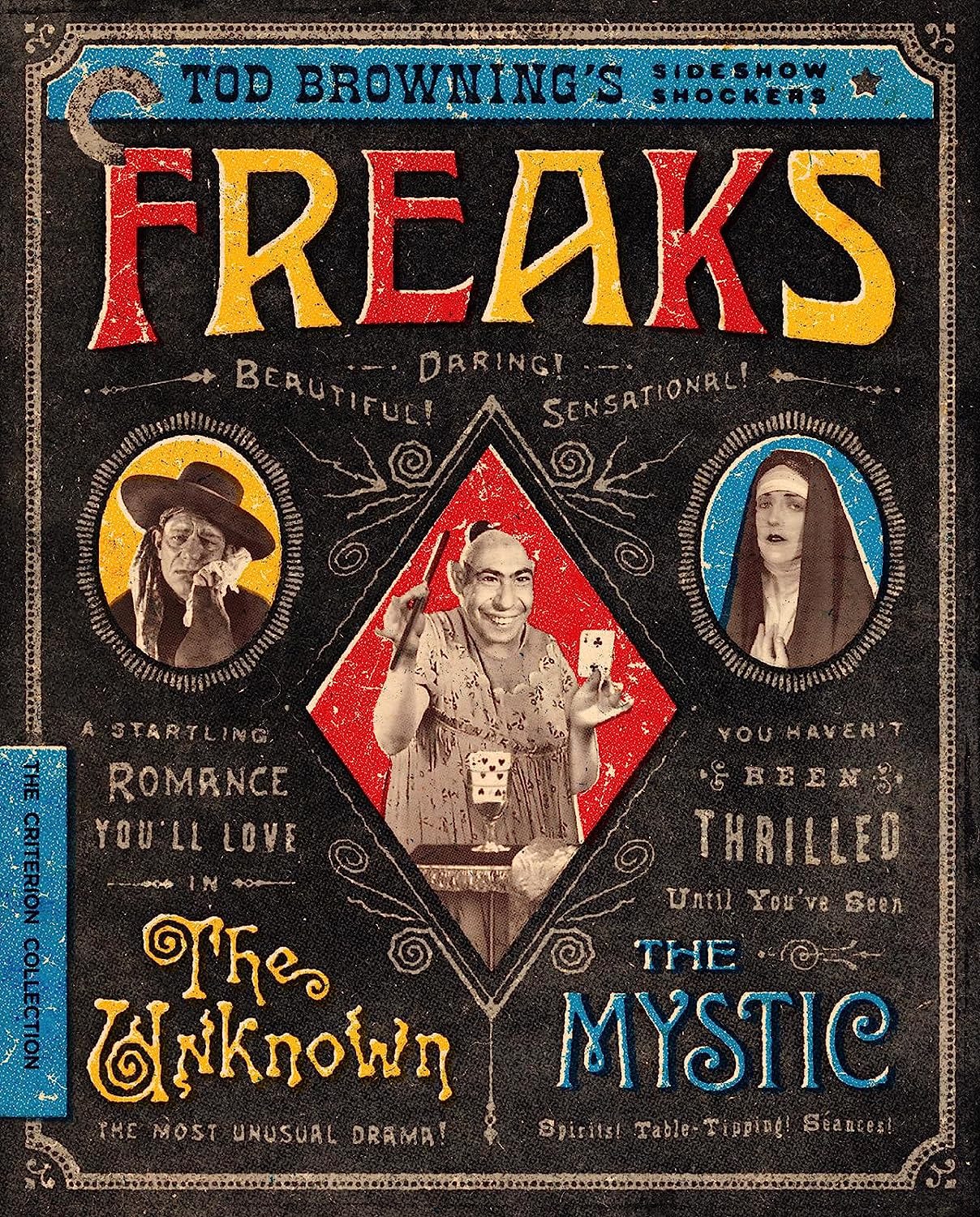

Freaks / The Unknown / The Mystic: Tod Browning’s Sideshow Shockers

October 17, 2023

Just in time for Halloween. 🎃

“The world is a carnival of criminality, corruption, and psychosexual strangeness in the twisted pre-Code shockers of Tod Browning. Early Hollywood’s edgiest auteur, Browning drew on his experiences as a circus performer to create subversive pulp entertainments set amid the world of traveling sideshows, which, with their air of the exotic and the disreputable, provided a pungent backdrop for his sordid tales of outcasts, cons, villains, and vagabonds. Bringing together two of his defining works (The Unknown and Freaks) and a long-unavailable rarity (The Mystic), this cabinet of curiosities reveals a master of the morbid whose ability to unsettle is matched only by his daring compassion for society’s most downtrodden.”

TWO-BLU-RAY SPECIAL EDITION FEATURES

New 2K digital restoration of Freaks, with uncompressed monaural soundtrack

New 2K digital reconstruction and restoration of The Unknown by the George Eastman Museum, with a new score by composer Philip Carli

New 2K digital restoration of The Mystic, with a new score by composer Dean Hurley

Audio commentaries on Freaks and The Unknown and an introduction to The Mystic by film scholar David J. Skal

New interview with author Megan Abbott about director Tod Browning and pre-Code horror

Archival documentary on Freaks

Episode from 2019 of critic Kristen Lopez’s podcast Ticklish Business about disability representation in Freaks

Reading by Skal of “Spurs,” the short story by Tod Robbins on which Freaks is based

Prologue to Freaks, which was added to the film in 1947

Program on the alternate endings to Freaks

Video gallery of portraits from Freaks

English subtitles for the deaf and hard of hearing

PLUS: An essay by film critic Farran Smith Nehme

click her to buy the Tod Browning Collection

THE BEST OF SEPTEMBER Some of the best of what I watched, read and listened to last month. . .

BOOKS

Garbo by Robert Gottlieb

“In Garbo, the acclaimed critic and editor Robert Gottlieb offers a vivid and thorough retelling of her life, beginning in the slums of Stockholm and proceeding through her years of struggling to elude the attention of the world―her desperate, futile striving to be “left alone.” He takes us through the films themselves, from M-G-M’s early presentation of her as a “vamp”―her overwhelming beauty drawing men to their doom, a formula she loathed―to the artistic heights of Camille and Ninotchka. He examines her passive withdrawal from the movies, and the endless attempts to draw her back. And he sketches the life she led as a very wealthy woman in New York―“a hermit about town.”

Whitley Heights Walking Tour

Before Beverly Hills existed the rich and famous stars of Hollywood lived in a Mediterranean style neighborhood called Whitley Heights. This gem of a neighborhood still remains today and is virtually untouched. Justin Root takes us on a chatty and educational walking tour through this historic neighborhood.

MUSIC

It's fall, and nothing sets the scene better for this mysterious and melancholic season than Pino Donaggio's haunting and eloquent score for Nicholas Roeg's 1973 film 'Don't Look Now'.

New on the Bookshelf

Universal Horrors: The Studio's Classic Films 1931-1946 by Tom Weaver, Michael Brunas and John Brunas

“Trekking boldly through haunts and horrors from The Frankenstein Monster, The Wolf Man, Count Dracula, and The Invisible Man, to The Mummy, Paula the Ape Woman, The Creeper, and The Inner Sanctum, the authors offer a definitive study of the 86 films produced during this era and present a general overview of the period.”

click here to purchase Universal Horrors

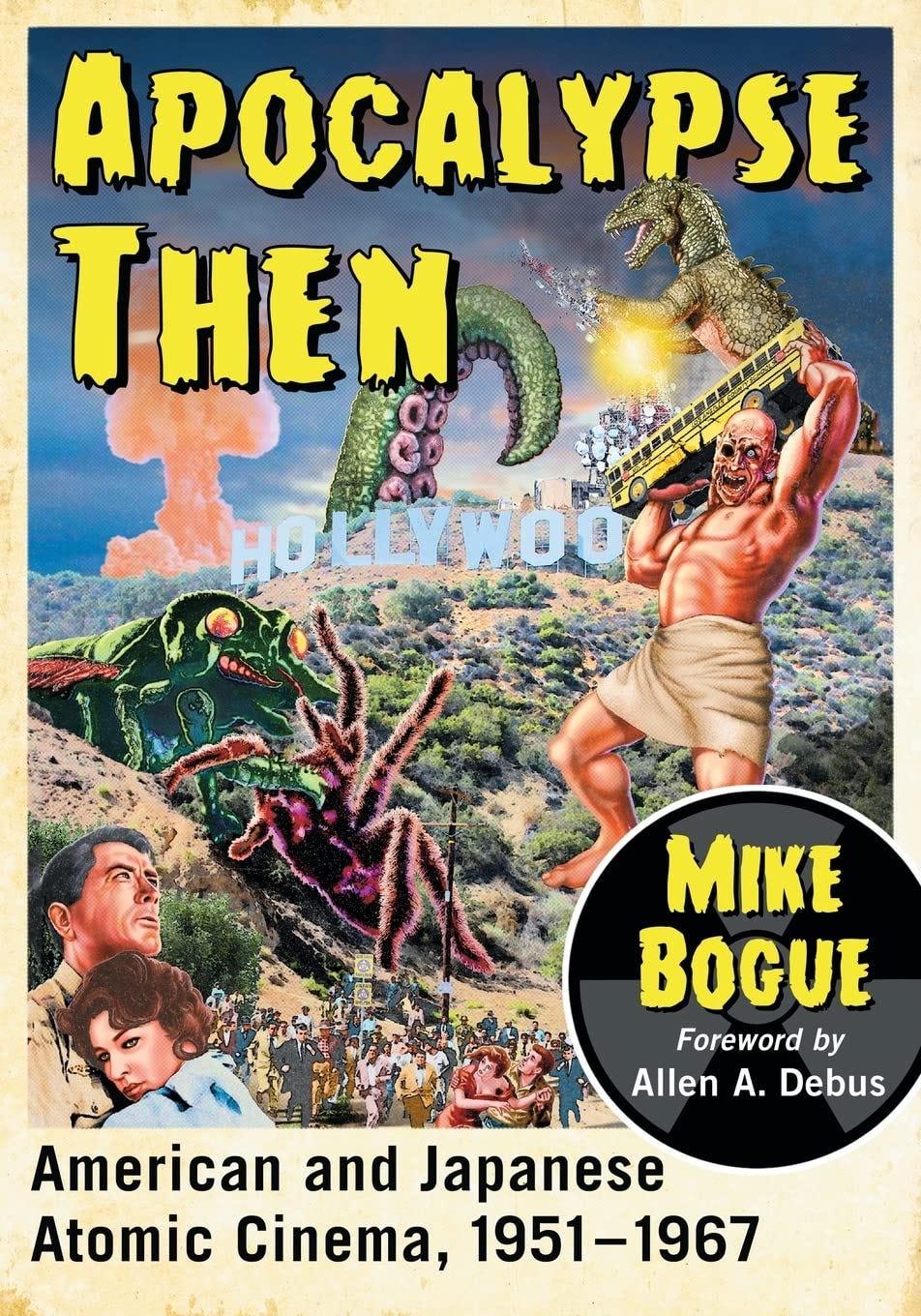

Apocalypse Then: American and Japanese Atomic Cinema, 1951-1967 by Mike Bogue

“American science fiction movies of the 1950s and 1960s generally proclaim that it is possible to put the nuclear genie back in the bottle. Japanese films of the same period assert that once freed the nuclear genie can never again be imprisoned. This book examines genre films from the two countries released between 1951 and 1967--including Godzilla (1954), The Mysterians (1957), The Incredible Shrinking Man (1957), On the Beach (1959), The Last War (1961) and Dr. Strangelove(1964)--to show the view from both sides of the Pacific.”

click here to purchase Apocalypse Then

and finally. . .

Cinema Cities is a one woman show written, produced, edited, researched, designed all by me, Sydney. If you’re loving this content please consider supporting Cinema Cities by becoming a paid member of this substack (you get cool extra stuff) or clicking here and joining my Patreon⭐️ (same cool extra stuff as the paid substack)

You can find a list of essential Cinema Cities books and movies here: Cinema Cities Favorites

🎵Like the music featured in the videos on the channel?

you can find a playlist with the music I've used here: CINEMA CITIES PLAYLIST

(And, if you sign up to Epidemic Sound through the playlist link, you'll get 1 month for free!)

I hang out on Twitter so come on over and say hi!

Email: CinemaCities1978@gmail.com

Disclosure: I may receive a commission or referral bonuses for purchases or sign-ups made through my links. I am a participant in multiple affiliate and referral programs, including Amazon and Epidemic Sound.

To call the Little Ferry fire catastrophic is a massive understatement.

I knew nitrate film decomposed, and films made on it were flammable, but the value of the amount of material lost because of fires is incalculable. So no wonder good prints of many silent films are scarce now!

Great article. Scorsese touched upon the tragic loss of (silver nitrate) films of the French pioneer George Méliès in "Hugo". Theda Barra was a huge star who dominated silent, pre-code movies, but most of us have barely seen anything about her.

I strongly STRONGLY recommend you all see "Dawson City: Frozen Time" for a complementary perspective on the lost (and in this case, found) archives of early film. It is a true story too fantastic to comprehend. The found footage includes a short newsreel scene of the (thrown) 1919 World Series that is priceless to baseball historians.