What Stars Will Survive Television: 1939

Change is in the air: the shake-up may be delayed, but it’s inevitable

Popular belief holds that television entered the mainstream after World War II and, by 1950, was already disrupting the motion picture industry. However, concerns about television’s potential to upend Hollywood were being discussed within the film community—and even in fan magazines—as early as 1939.

Before World War II, television broadcasts were experimental and limited in scope, with only a few cities having access to the technology. But after the war, television would become more accessible and affordable to households across America, ultimately becoming a dominant form of entertainment by the early 1950s. The growing prevalence of television sets in American homes would mark a dramatic shift in how people consumed entertainment, and this shift did not go unnoticed in Hollywood.

In 1939, New York World's Fair unveiled the first public demonstration of television technology, sparking widespread fascination and laying the groundwork for its future role in American homes. It was at this moment that Hollywood began to confront the growing potential of television, which seemed to promise an alternative form of entertainment, and perhaps a competitor to the film industry itself. Television technology had been in development for years, but the 1939 Fair marked the first time the public had a glimpse of it on such a grand scale. Though it was still in its infancy, the demonstration of television at the Fair left many in Hollywood wondering what the future might hold.

Some in Hollywood saw television as an exciting opportunity to broaden the appeal and visibility of stars who could adapt to the new medium. But others recognized the looming threat: another seismic technological shift that could spell chaos and disruption, much like the arrival of sound films. The transition to sound upended the entire movie ecosystem, ruining careers, bankrupting studios, and crippling motion pictures evolution in a specific artistic direction. Television was seen as the next impending apocalypse.

However, not all critics viewed the anticipated upheaval negatively. They believed that television, with its close-up imagery (a result of technological limitations), would become the true measuring stick for talent.

Personality stars might suffer, but real thespians with skill and a finely honed craft would flourish. Additionally, those with an unquantifiable appeal—what some would call “oomph”—would thrive.

The concerns expressed in the film community, echoed in fan magazines, were not just about the immediate future but about the deep, lasting effects of television on the motion picture industry. This is evident in the article that follows, which captures the early discussions about television’s role in Hollywood as the industry began to anticipate the changes ahead.

What Stars Will Survive Television Motion Picture Magazine October 1939

by William F. French

HOLLYWOOD is more jittery than ever before. It knows an upset is in the offing that will make the topsy-turvy days of the advent of talking pictures seem like a drowsy June afternoon.

The town is seething with an undercurrent of excitement and fear. Not knowing what to expect, the villagers gather on the street corners expecting it. Anticipation and apprehension walk hand in hand, with everybody ready to jump to cover.

This tension isn't caused by fear that the government is getting too curious about things the studios would like to have forgotten, even if executives are making regular trips to Washington for "little chats" that aren't fireside. It goes deeper than politics, business conditions, or the steady decline in box-office receipts. The town senses that overnight there is going to be another of those amazing Hollywood revolutions that put the "ins" out and the "outs" in.

But this time it is going to be a shake-up of whole industries, not merely of individuals. Many believe that the thing about to happen will wash up pictures, while others are certain it will write "finis" to radio.

For television has rounded the corner. It has knocked off the lid radio and pictures have had clamped on it. Right now, it's spitting on its hands, preparatory to digging in.

Television, as radio eagerly assures us, is far from perfect and has decided limitations. Oh, yes, very decided.

But Hollywood has had experience with other things that weren't ready, and that then broke the bounds that were strangling them. Also, it knows a few people familiar with television in Europe and has read about the twelve-by-fifteen foot television screens being installed by Gaumont British in London movie theatres. So Hollywood has decided to do a little worrying—Hollywood is reeking with fear. Who will get the juicy jobs of television? Hollywood is dripping anticipation. And the old silent picture stars are enjoying the first laugh they've had in years, for sight on the air is going to sound taps for certain stars of today (especially radio stars), just as sound on the screen did for them.

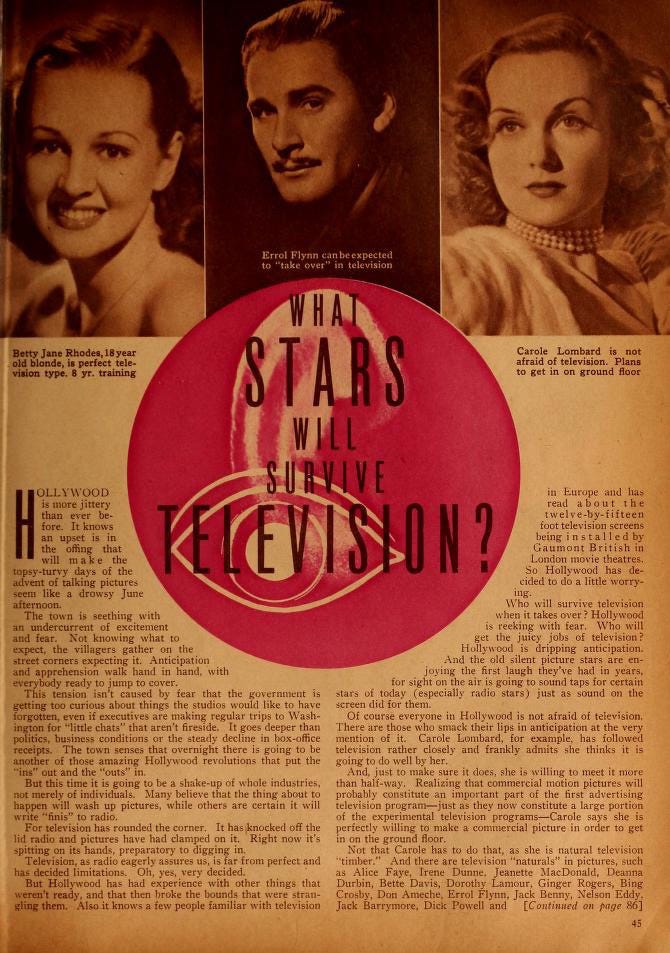

Of course, everyone in Hollywood is not afraid of television. There are those who smack their lips in anticipation at the very mention of it. Carole Lombard, for example, has followed television rather closely and frankly admits she thinks it is going to do well by her.

And, just to make sure it does, she is willing to meet it more than halfway. Realizing that commercial motion pictures will probably constitute an important part of the first advertising television program—just as they now constitute a large portion of the experimental television programs—Carole says she is perfectly willing to make a commercial picture in order to get in on the ground floor.

Not that Carole has to do that, as she is natural television "timber." And there are television "naturals" in pictures, such as Alice Faye, Irene Dunne, Jeanette MacDonald, Deanna Durbin, Bette Davis, Dorothy Lamour, Ginger Rogers, Bing Crosby, Don Ameche, Errol Flynn, Jack Benny, Nelson Eddy, Jack Barrymore, Dick Powell, and Burns and Allen. These, together with a dozen other movie stars and a score of movie players, can be depended upon to “take over” at the cost of radio stars now popular on the air but who haven’t the personal appearance and acting ability necessary for visual entertainment. It requires more than just good radio voices for television—as television, like pictures, demands personality and “oomph.”

AS TELEVISION'S scope and needs increase, there will naturally be opportunities for newcomers as well as for old-established stars.

Because this medium of entertainment cannot reproduce depth and detail as the movie camera does, it must depend upon close-in action and convincing acting. It cannot utilize striking sets, great mob scenes, unusual effects, and lavish costumes to supply glamour and offset lack of real dramatic ability. Consequently, sincerity, vivacity, sparkle, and personality will be at a premium.

In television, players will not be carried to unearned stardom as they have been in pictures, and the assembling of powerful casts will not permit a star who has outgrown his or her usefulness to stay up in the top brackets. Television will not furnish glamorous situations and backgrounds to oversell players—as recently happened to one girl whose subsequent picture was so bad that, to quote a director from the studio that made it: "we had to make retakes before we could put it on the shelf."

This will be favorable to performers such as Bette Davis and disastrous to those who are little better than clothes-horses or mannequins in exquisite surroundings.

Those who have worked with television, such as directors and studio casting officials, know there is a personality "oomph" that stands out in television. They say that television will discover not only new personalities but new types of personalities.

ALREADY those with hopes realize that it is not a question of being a blonde or a brunette or a redhead (make-up being able to cover any color deficiency in television), but how much sparkle is in your eyes and what depth of feeling your face can express.

Temporarily, at least, due to the small size of the screens on home receiving sets, intimate action and close-ups will predominate in television programs—just as they do today. This will exclude those radio performers who have been found unfit for motion pictures. By the time television has advanced to the stage of using more long shots, even though that be but a matter of a few months, motion picture and legitimate stage players and stars will have filled all the important spots, leaving very little chance for those radio stars who do not photograph or act well to break in.

Of course, there are some air stars, such as Ameche, Benny, Cantor, Burns, Lamour, Burns and Allen, who have "visual personality." But after spending six years and millions of dollars trying to develop radio players for pictures, the movies have been able to induce the public to accept less than a dozen.

That accounts for some of the apprehension in Hollywood. Hundreds of radio performers making their living before the microphone here are as unfitted to go before the televiewer as they are to face the movie camera. They realize that once television is in, they are out.

Add to this the fact that radio realizes that once an important television broadcast goes on the air, radio programs go into discard, and that now even talk of television seriously hurts the sale of radio sets, and you will understand why this industry dreads visual broadcasts. Without a clear-cut idea of how it can collect on the new, it faces the complete disorganization of the old.

So the movies joined hands in concentrating on no progress for television. Foolishly but fervently. During the last six months, however, there are those in the industry who have doubted the wisdom of retarding television and keeping us years behind Europe in this important development. And there are also those who realize that television will not be an enemy of motion pictures but will serve them mightily. They feel that it will be the means by which motion pictures dominate the air and completely outrank every other medium in entertainment, education, and the job of keeping the whole world within sight as well as within sound.

FOREMOST among these is Eddie Cantor. Five years ago he told the writer that he was preparing for television, looking eagerly forward to the day when great shows, using more stars than anyone had ever dreamed of assembling in a single performance, would be put on film and broadcast throughout the country. Shows that would give Hollywood greater production than it ever before knew.

Eddie was not merely weaving wild dreams. He was looking directly into the future. For three years, the Don Lee Television Broadcasting System has been broadcasting motion picture newsreels, shorts, and cartoons. Every day commercial motion pictures are sent out from New York City by television.

In England and Germany, cinema audiences have for months been seeing motion pictures on theatre-size television screens. Pictures sent to hundreds of theatres and thousands of homes in a single broadcast.

RKO'S special television short and trailer made from the picture Gunga Din was the first contribution by any major studio to this vitally important development. Antagonistic to television, Hollywood hid its head in the sand until circumstances compelled it to sit up and take notice. Even today, less than half the motion picture executives realize that television offers them the greatest opportunity of their lives.

But fortunately, the progressive ones press ahead. Gregg Toland, Samuel Goldwyn's ace cameraman, is planning a television short version of their next picture, and Sam has bought the rights to an invention for the securing of third dimension on film that they feel will add a great deal to the depth and quality of television pictures.

HOLLYWOOD is beginning to stir itself, and stars and players are straining at the leash. They know what television means to them. They can't get into "visual" entertainment quickly enough.

Some of the studios are moving forward. Others are holding back. Paramount is not only equipping its new studios for television, but has secured a controlling interest in the Dumont Television Corporation.

Paramount-Dumont already has a telecasting station in Passaic, New Jersey, which it plans to move to New York City. Even under the present restricted television broadcasting range of about thirty-five miles, a telecasting station in New York City can reach over ten million people.

Until the telecasting range is increased, the very cost of putting in expensive coaxial cable to carry television programs from station to station works to the benefit of motion pictures. For by putting television programs on film, they can be sent air-express to the telecasting stations and from there put on the air.

At present, the theatrical interests in New York are far more alert to the possibilities of television than is the average motion picture studio, and many writers, players, and theatrical producers in the big city are working on television shows. They plan to put out shows that can go to the various television studios and be televiewed in the flesh.

BUT meanwhile, the demand is for motion picture film for telecast.

Motion picture players, from extras to famous stars, are impatient with the quaking executive who divides his time between worrying about what television will do to the theatres of the country and assuring himself that it's just a whim that will wear itself out, and that it isn't practical anyway.

Sensing an eagerness to learn about television, to prepare for it, and knowing that sooner or later they will be face to face with the problem of making up their players to go before the televiewer for personal appearance on the air, the Westmore Brothers, makeup experts for four different Hollywood studios, have created a television makeup.

Hollywood's great horde of teachers, schools, and coaches have added "preparation for television" to their curriculum. Little theatres are developing one-act plays with television technique . . . Studio cameramen and electricians are studying television technique of lighting, and directors and writers are giving attention to intimate scenes that can be lifted out for telecast.

Artists' agents have already added television clauses to their contracts, and studio casting directors are beginning to regard movie aspirants with an eye to their television possibilities.

The air is charged with excitement, anticipation, wonderment, and with the usual share of skepticism, too. There has been so much adverse propaganda in connection with television. But if it moves so steadily forward, there must be some irresistible force behind it.

and finally. . .

Cinema Cities and the Screen Spectator is a one woman show written, produced, edited, researched, designed all by me, Sydney. If you’re loving this content please consider supporting Cinema Cities by becoming a paid member of this substack (you get cool extra stuff) or clicking here and joining my Patreon⭐️ (same cool extra stuff as the paid substack)

You can find a list of essential Cinema Cities books and movies here: Cinema Cities Favorites

Check out my YouTube channel here

🎵Like the music featured in the videos on the YouTube channel?

you can find a playlist with the music I've used here: CINEMA CITIES PLAYLIST

(And, if you sign up to Epidemic Sound through the playlist link, you'll get 1 month for free!)

Email: CinemaCities1978@gmail.com

Disclosure: I may receive a commission or referral bonuses for purchases or sign-ups made through my links. I am a participant in multiple affiliate and referral programs, including Amazon and Epidemic Sound.

The Eddie Cantor part is extremely interesting! I’ve studied Cantor and have read a lot about him and he was always one of the first people to hop on some new trend or creative idea. For example, when the stock market crashed, he quickly wrote some best selling short comedy books. And of course, Cantor did eventually become a host of the Colgate Comedy Hour in the 50s. Very unsurprising that he was eager to join the world of television in the 30s.

Michael Eisner regarding the movie studios response to television:

"The movie studios tried to ignore it, dismiss it, then fight it, and ultimately embraced it.”

Reading old issues of THE BILLBOARD and VARIETY, the above line applies to the responses of others, to each new technology (listed below) thru the decades.

The Phonograph

Radio

Talking Pictures

Television

Internet